Mar 9, 2022

Modern Versions of Laws in the Ramayana and the Mahabharata

Sumeysh Srivastava

The days leading up to Diwali are perhaps the most festive time period in the Hindu Calendar. Symbolizing the victory of light over darkness, this is the time when people decorate or renovate their homes, get new clothes made and exchange gifts with relatives. This is also a time when stories related to ancient Indian literature, primarily the Ramayana are revisited, in different forms, including Ramlila performances across the country. Diwali has many origin stories and legends linked to it but is primarily known as the day when Lord Rama returned home to Ayodhya after defeating the Demon-King Ravana.

In this blog, we look at certain incidents and rules mentioned in various stories in ancient Indian literature, through the lens of modern laws and rules. We have limited ourselves to two frameworks; first, where rules given in these epics can be traced to modern day legal rules and second, where we have looked at how current Indian laws would apply in some of the situations mentioned in these stories.

Ancient Indian Literature and Modern International Law

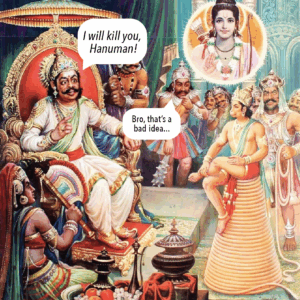

Before engaging in the war with Lanka, Rama sent Hanuman as an envoy to Ravana’s court in an effort to ensure a peaceful return for Sita and to avoid warfare. Ravana planned to use this opportunity to kill Hanuman. However, he was reminded by his brother Vibhishana that killing an ambassador or an envoy goes against Rajdharma, or the duty of kings. This principle is mirrored in Article 29 of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations 1961 which regulates diplomatic immunities and privileges. The article clarifies that a diplomatic agent cannot be arrested or detained. She has to be treated as a guest of the state and all steps must be taken to ensure that she is not harmed in any way.

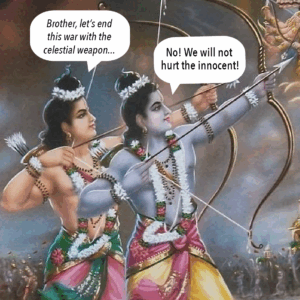

During the war against Ravana, Lakshmana was forbidden by Rama to use a weapon of mass destruction, which would have destroyed all the Lankans, including those who were not armed. Similarly, in the Mahabharata, Arjuna refrained from using Pasupathastra in the war against the Kauravas. Similar provisions are found in the Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, as well as customary international law. The principles of distinction and proportionality are recognized as part of customary international law. According to these principles, warring parties/states are prohibited from using any weapon that would cause an excessive injury to the unarmed civilian population that cannot be justified as gaining a military advantage. Article 51(4) of the Additional Protocol 1 to the Geneva conventions prohibits indiscriminate attacks on civilians. Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court also covers this under the definition of war crimes.

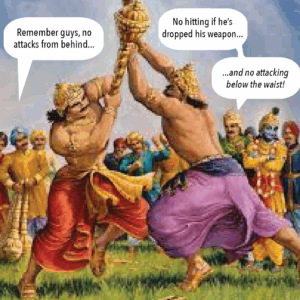

The Rig Veda contains certain rules which state that it is “unjust to strike someone from behind, cowardly to poison the tip of the arrow, and heinous to attack the sick or old, children, and women”. Similar provisions are found in Article 16 of the Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, Article 35 of the Additional Protocol 1, and Articles 3 and 6 of Protocol II to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons. For example, dumdum bullets, which expand after impact are banned under this provision. The idea behind this provision is that you should not cause any superfluous injury that goes beyond gaining a military advantage.

In the Mahabharata, there is a reference to Dharma-Yuddha, which talks about certain rules of warfare, which for a fair and righteous war. A few examples are fixing times for warfare, not killing an injured warrior, protecting prisoners of war, etc. Similar provisions can be found in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which discuss the rules for the regulation of land warfare.

The Agni Purana text states that a soldier who surrenders by laying down his weapons should not be slain and medical assistance should be given to the wounded soldiers of the enemy. Provisions can be found, across various conventions which form a part of customary international law, which talk about the provision of basic necessities to prisoners of war.

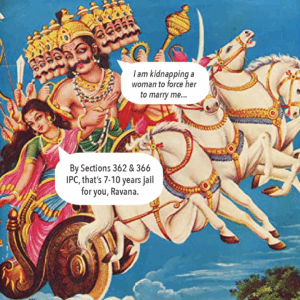

Ancient Indian Literature and application of modern Indian Criminal Law

The main reason for Rama’s war with Ravana is the kidnapping of Sita by Ravana. Sita was tricked into stepping out of the protective circle created for her by Ravana and taken to Lanka against her will. Such an act today would attract sections 362 and 366 of the Indian Penal Code. Section 362 deals with the abduction and punishment of up to 7 years in jail are provided. Further, section 366 talks about kidnapping a woman to compel her for marriage and carries a punishment of up to 10 years.

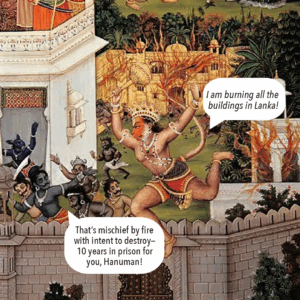

One of the most famous episodes in the Ramayana is the burning of Lanka by Hanuman. As per legend, Ravana tries to insult Hanuman by not offering him a seat in his court. Hanuman, however, just extends his tail and makes a seat, which turns out to be taller than Ravana’s throne. Enraged, Ravana orders Hanuman’s tail to be set on fire. However, this is counterproductive since Hanuman does not feel pain and basically runs around setting fire in all of Lanka. Today an action like Hanuman’s could attract Section 4 of The Prevention of Damage to Public Property Act, 1984, which talks about damaging public property by fire or explosive substances and attracts a punishment between one to 10 years in jail. It would also attract Section 436 of the Indian Penal Code, which has a similar provision of mischief by fire.

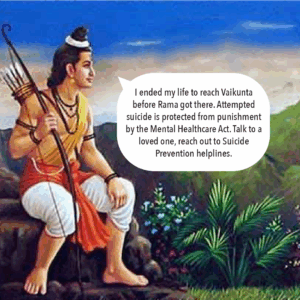

Laxmana chose to end his life in the Sarayu river after disobeying an order given by Rama. Previously, according to Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code, anyone who attempted to commit suicide could be punished with imprisonment for up to one year and/or a fine. However, section 115 of the Mental Healthcare Act invalidates section 309 and states that regardless of section 309, any person who attempts to commit suicide is presumed to have severe stress, and will not be tried and punished. The government has a duty to provide care, treatment and rehabilitation to a person having severe stress who has attempted to commit suicide, to reduce the risk of another suicide attempt by that person.

Shurpanakha, the sister of Ravana, went to see Rama at his hermitage where she transformed from a red-haired demon into a beautiful woman to talk to him. Initially, after Rama decided not to talk to her, she decided to approach his brother, Lakshman. After Lakshman insulted her, Shurpanakha in anger tried to attack Sita who was Rama’s wife. At this point, Lakshman immediately pulled out his sword and cut off the nose and ears of Shurpanakha. If Lakshman had done something like this today, then the police would have arrested him for causing grievous hurt to Shurpanakha. This is a crime under Section 320, of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. A person is punished for the crime of grievous hurt if they do any of the following: (a) emasculation, i.e., removal of sexual organs, (b) depriving someone of their eyesight or hearing (c) hurting or permanently damaging any body part or joints on the (e) permanently disfiguring someone face or head (f) fracturing or dislocating any bones or teeth on a person.

There may be other incidents and rules that can be looked at in this manner, across religious texts, so feel free to add your suggestions in comments.

With contributions from Sruthakeerthy Sriram, Shonottra Kumar, and Malavika Rajkumar.