Feb 14, 2022

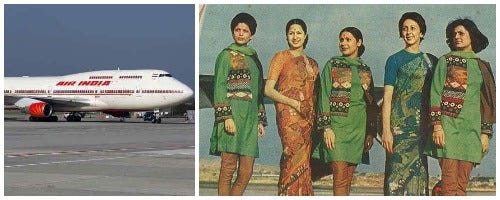

Gender Discrimination in the High Flyers Club: Indian Air Hostess’ Battle for Workplace Equality

Shonottra Kumar

Have you ever heard of people criticising Air India for having ‘older’ air hostesses? They often try to justify their statement with further misogynistic remarks of there being an unspoken standard set by the industry of having certain kind of women be air hostesses — the pretty and young with just the right hair and makeup. They claim it to be a part of the air travel experience. But little do these people know that there is a story of a great struggle for women’s rights and equality there.

This story is not like any other legal battle you know of. It took place over a span of 30 years, with many cases filed before tribunals, high courts and supreme court and in many phases. Hereunder are the judgments passed through the years that narrate this struggle.

1982: Air India v. Nargesh Meerza

The judgment of the Nargesh Meerza case marked the first phase of the struggle.

The retirement age of air hostesses was 35 years, much lesser than their male counterparts who had their retirement at 58 years, and was raised to 45 years by the Supreme Court in 1982. While this order may have been seen as a progressive step, the relief granted under it was only momentary. This Supreme Court order came with its own evils, the most obvious one being that there still was no equality.

A much deeper examination of the judgement reveals the true nature of bigotry that existed back then. It justified the discrimination between male air flight pursers and female air hostesses by saying that they were different cadres and different rules and conditions of service apply to each of these cadres.

Under labour law and service rules, it is true that different cadres and classes exist to which different rules of hiring, firing and promotions apply, and that in itself is not a violation of the principle of equality, but this order failed to recognise that this classification in cadre was based on sex discrimination ab initio.

It is an acceptable practice for having different rules for different classes of employees, but the Court failed to see that this differentiation between these classes, flight pursers and air hostesses, was on the basis of sex, thus violating Article 14 of the Indian Constitution.

Other atrocities against air hostesses that the Court gave its sanction to were restrictions on marriage before a certain age and years of service, restrictions on having children in the first four years of marriage, a limit on the number of children they could have, etc. Non-observance of these restrictions could legally render them terminated from employment. The worst oppression of all was that despite having plenty of experience, air hostesses were not given supervisory positions. Seasoned female air hostesses were made to answer trainee flight pursers, presuming their inferiority on the basis of their gender.

The 1990s: Cases and Government Directions that followed Nargesh Meerza

After 1982, several independent petitions went before various High Courts and the Supreme Court requesting to set aside the Nargesh Meerza judgment for violation of fundamental rights of equality and other constitutional freedoms, further demanding parity with male flight pursers.

One particular case (Lena Khan v. Union of India) even pointed out that this discrimination existed only against Indian employees of the company. They used the examples of the twelve European and one Japanese air hostesses employed by Air India whose retirement age was at par with their male counterparts in their respective countries. As a knee jerk reaction to this petition, those air hostesses above the age of 45 were let go off globally. This petition, along with many others, did not succeed, thus upholding the decision of 1982.

Alternatively, air hostesses made a representation to the Parliamentary Committee on Petitions. In 1989, upon receiving the recommendations of this Committee, the government issued directions to Air India to allow both male and female cabin crew to serve till the age of 58. The company responded to these directions by sending a detailed letter to the government requesting to reconsider its directive by stating various agreements and settlements reached between employees and employers on different conditions of service for flight pursers and air hostesses. Ultimately the government altered its directive and granted the company discretion to ground air hostess after a certain age, but ensured continued employment for these women till the age of 58.

In light of these directives, in 1990, Air India issued a circular stating that air hostesses who had achieved the age of 45 would be offered ‘suitable on ground positions’. In 1993, this was further extended to 50 years, subject to medical fitness clearance.

The end result of the bureaucratic process was also just a partial win, as they were still not considered as equals in their workplaces.

2003: Air India Cabin Crew Association (AICCA) v. Yashaswanee Merchant

The turn of the century came and women in India were still seen fighting for rights that the global west had achieved decades ago. In the middle of hectic shifts on flights and managing their personal lives, they made sure to take out time to continue their fight.

Some hope was seen by an order of Bombay High Court delivered by Justice AP Shah, where it was held that the service conditions between male and female cabin crew were discriminations based on their sex and violative of Articles 14, 15 and 16 of the Indian Constitution. However, in 2003, this was overturned by the Supreme Court in Air India Cabin Crew Association v. Yashaswanee Merchant and Ors.

The Court noted that most of the female air hostesses fell under the ‘workmen’ category whose terms and conditions of service including the age of retirement is governed by the agreements and settlements made between the union and the employer as per industrial disputes law. It further upheld that different ages of retirement and salary structure for male and female employees in Air India were based on their different conditions of service, and that there was no discrimination on the basis of sex.

At that time, the female membership of AICCA was seen to be over 600 air hostesses supporting the disparate rules as opposed to the 50 odd women against it. What most people failed to understand at that point was that popularity in numbers does not determine the legality of a situation, neither does it negate constitutional protections.

This Supreme Court order was a huge step back, but it did not deter the air hostesses from continuing to fight.

2012: AICCA v. Union of India

After the Yashaswanee Merchant judgement was delivered, on 21st November 2003, the Government issued a directive negating this order and all past directives allowing policies to be made for equal treatment of female cabin crew. Following this directive, Air India issued an office order indicating that the flying age of female cabin crew be brought up at par with male cabin crew and liberties be given to the in-flight service department to assign flight duties to such air hostesses who were grounded at the age of 50. Air hostesses were now allowed to be in-flight supervisors as well.

AICCA challenged this decision of the company before the Delhi High Court in 2006. It is difficult to understand whether their aggravation was based on actual legal contentions or the threat to patriarchy and control of women. Dismissing their petition, the Delhi High Court made an important observation that the position of ‘In-flight supervisor’ was, in fact, a description of job function and not a post exclusively reserved for male cabin crew.

They filed an appeal against the Delhi High Court order and the resultant Supreme Court order was the final nail in the coffin of this particular battle.

The Supreme Court order delivered by Justice Altamas Kabir in AICCA v. Air India, amongst other things, sided with the decision of the company to treat male and female cabin crew at par with each other. It noted that Air India was at liberty to make and revise policies that intended to benefit all employees.

With all the privilege and resources available at their disposal, it still took these air hostesses over three decades to achieve equality at their workplace. Theirs is just one of the many examples of what women face in different sectors all over the country.

Even with having explicit and codified fundamental rights of equality and protection from discrimination, Indian women find it extremely difficult to exert these rights in practice. The next time you decide to pass comment on an air hostess’s age or know someone doing the same, remember this three-decade long struggle and what it took for that air hostess to be your purser!

References

Air India v. Nargesh Meerza and Ors (1981) 4 SCC 335

Lena Khan v. Union of India (1987) 2 SCC 402

Air India Cabin Crew Association v. Yashaswanee Merchant and Ors. (2003) 6 SCC 277

Air India Cabin Crew Association and Ors. v. Union of India and Ors. (2012) 1 SCC 619